Padmaavat Review: Much Ado About Nothing

I recently watched Sanjay Leeela Bhansali‘s magnum opus, Padmaavat, for a good three hours, and there was just one question that lingered in my mind throughout – why was there so much noise by the Hindu political parties in India? In my opinion, the Muslims of the subcontinent should have been angered by the way Alauddin Khilji – a great Muslim warrior and the Sultan of Delhi has been demonised in the film. It would be safe to say, that this movie not only undermines the feelings of Muslims, but questions Bhansali’s professionalism to a large extent.

Moreover, historians would also not agree to the way Alauddin Khalji has been portrayed in Padmaavat. Throughout the film the historic leader has been depicted as a savage and successfully defaced, when in reality, he was known as an able warrior and conqueror, to say the least.

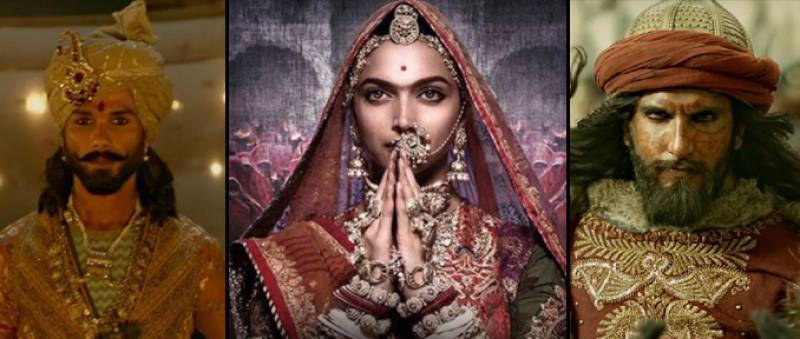

Ranveer Singh, the antagonist who plays the role of Khilji, acts barbarian through his physique, diction and even mannerisms. Gnawing the meat of the bone like a carnivore, carrying beheaded warrior heads, bearing hair chest with cold rimmed hungry eyes is nothing short of portraying a lustful beast – a perennially dirty faced villain on the film screen, stomping his feet even during the popular Padmaavat dance number Khalbali.

It is odd but probably convenient for Bhansali to ignore Khilij’s umpteen conquests of many royal Indian estates and a befitting defeat to the Mongols as Sultan of Delhi.

The Rajput Queen Padmavati (Deepika Padukone) on the other hand emerges full of valour and bravery who has inscribed her name in the history of Rajputs – even though she is not a Rajput by birth but married to Maharawal Ratan Singh (Shahid Kapoor), King of Chittor, a scion of the Rajput dynasty who is always massaging his Rajput inheritance.

The two fall in love when Ratan Singh visits Singhal to collect precious pearls for his first wife and is accidentally wounded by Rani Padmavati who is out in the forest hunting deer. Smitten by her beauty, Ratan Singh returns to Chittor married to his new found love.

The story takes a turn when the priest at the Chittor Fort earns Ratan Singh’s displeasure and is ordered to be thrown out. He reaches out to Alauddin Khilji and persuades him to capture Padmavati, convincing him that his dynasty will flourish if Padmavati is by his side.

After laying siege at Chittor, a chain of events follow which ultimately bring the film to its controversial end. Ratan Singh is killed in the battlefield, Khilij’s army does a complete takeover of the Fort, and to save her honour, Padmaavati presides over a mass ‘jauhar,’ the practice of self–immolation prevalent at that time.

The upside of the film includes its grand scale cinematography, the depiction of Rajasthani palaces and temples detailing jharokhas, wooden doors and other ethnic motifs, bringing out the genius of Bhansali on film. Similarly, Padukone’s costumes are ethnic Rajasthani work, the intricate jewellery, though highly glamourised is stunning! The turbans and costumes of Ratan Singh and Alauddin Khilji also are a well-conceived and true depiction of Rajasthan and Turk Afghan heritage.

Surprisingly, what was missing in the film is the love affair for which Indian media and the religious and ethnic political parties were up in arms. To the dismay of the audience the romance between Alauddin and Padmavati is nowhere to be seen in the film; in fact, in a total of three hours, hardly two scenes include the presence of both in the same frame. Therefore, much ado about nothing. And lest we forget, Padmavati is famed to be a fictional character penned by Malik Muhammad Jayasi in a poem written 200 years after Alauddin Khalij’s death. In Ram Leela and Bajirao Mastani at least Bhansali had a correct historian on his side!

The views expressed in this article are not those necessarily of H! Pakistan

Have you had a chance to watch the movie?